Social Accountability and Frontline Health Workers can Help Us Realize the Right to Health

A group of people in Malawi meet to discuss the state of health services in their community, using CARE’s Community Score Card© approach. © 2015 CARE

By April Houston, Senior Program Officer, CARE

According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, every human being, anywhere in the world, is endowed with certain inalienable rights. In 1978, through the Alma-Ata Declaration, the global community further cemented one of those rights: the right to health. While the promise of the right to health is yet to be fully realized, the recent Primary Health Conference in Astana reaffirmed this right and the global community’s commitment to continue efforts to ensure it is fulfilled and upheld.

Despite these commitments, we know that half of the world still struggles to access quality health information and services, especially in rural, low-resource environments.

At CARE, one of the ways we work to ensure the right to health is the Community Score Card© (CSC). The CSC is a social accountability approach that brings together community members, health workers, and local government officials to discuss challenges to health access and service provision in their area, and to collaborate on finding solutions to barriers they identify. The process is designed to empower individuals to advocate for their right to health by holding governments and health workers accountable for the quality and equity of public health services in their communities.

First piloted in Malawi in 2002, the CSC has since spread to communities throughout Africa and Asia through a social enterprise that trains other organizations to facilitate the process.

In Malawi, we’ve seen significant impact in service utilization, provision, and satisfaction. One study found that pregnant women in communities that participated in the intervention received 20% more visits from health workers during their pregnancies than non-participants, and accessibility of reproductive and maternal health information increased by 22%. The CSC is particularly well‐suited to improving patient‐centered care, including building trust and strengthening relationships between communities and health workers.

But there’s much to learn about implementation of the approach and the health-related outcomes. New research evaluating our CSC approach, released last week in the journal BMJ Health Services Research, sheds light on this.

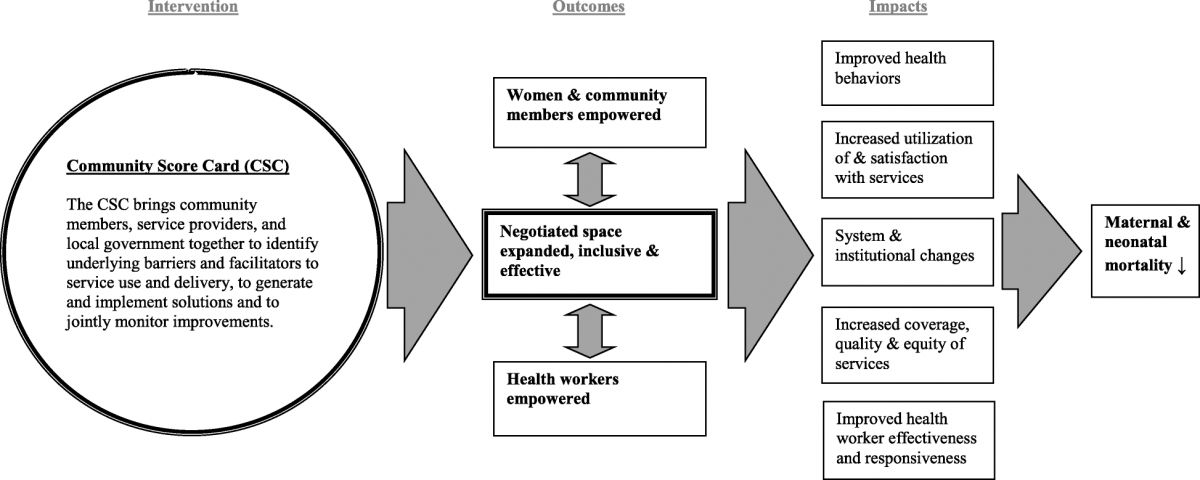

CARE’s theory of change (see below) posits that the empowerment of community members and frontline health workers—where they feel comfortable advocating for their rights—plus the creation of space for power-holders, health workers, and community members to talk and interact in a safe, supportive, and equitable environment, leads to improved health outcomes. To test this, a research team conducted an evaluation in Malawi to analyze the effect of the CSC on a set of governance measures, including trust in health workers, power sharing, mutual responsibility, and collective efficacy.

CARE's Theory of Change

The team found significant relationships between those who actively used the scorecard and perceptions of equity and quality of their discussions. They also found positive relationships with governance measures of actions resulting from the process, such as joint monitoring and transparency, collective action, and availability of community help.

“Active participation in the CSC ensures a safe, inclusive space to voice concerns and work together to improve health services and outcomes,” explained Sara Gullo, lead author of the article.

CARE Malawi’s Thumbiko Msiska agrees. “CSC enhances engagement of various stakeholders, especially rights-holders, and brings their perspectives into the conversations, clarifying expectations and promoting ownership.”

One unexpected result researchers uncovered was that CSC participation was “negatively associated with trust in health workers despite other evidence that the CSC improved relationships between health workers and community members.” The authors hypothesized that this could be attributed to promises made to community members but not kept by district health managers, which could be mitigated in the future by clearly communicating resource constraints and setting realistic expectations about what is possible.

Overall, the study concluded that CSC seems to influence key governance-related constructs that the researchers believe promote improved health behaviors, service accessibility and quality, and health worker effectiveness. In other words, when the voices of community members and frontline health workers are included in decision-making processes, demand for health services increases and their quality and equity improve, ensuring all are able to realize their right to health.